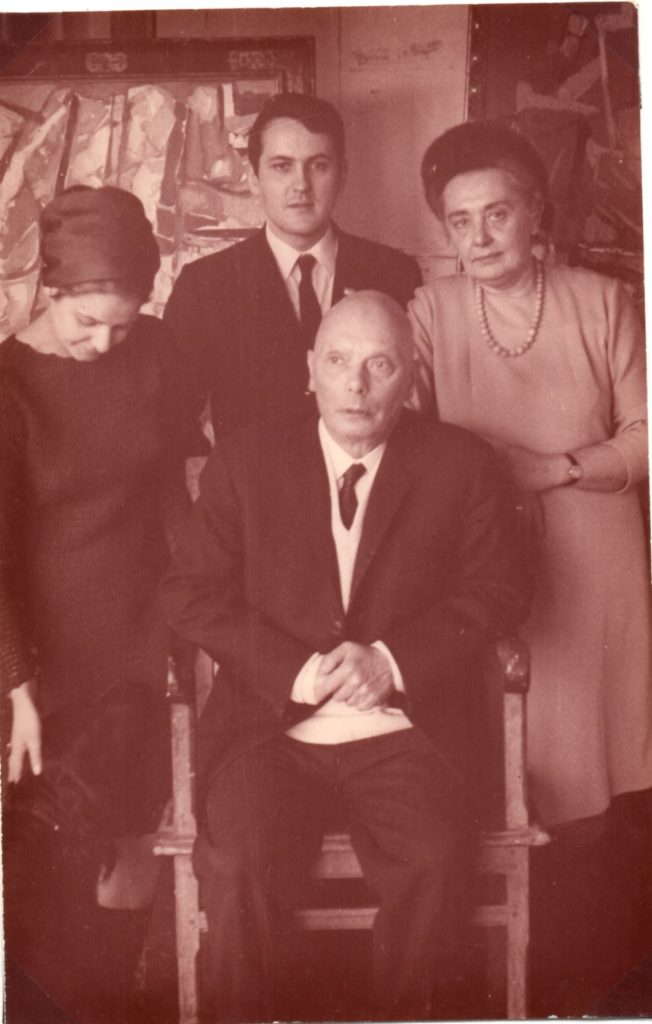

En hommage à Igor MARKEVITCH

« Le Compositeur et l’Homme »

par Jean-Claude MARCADÉ

Préfacier et organisateur d’un livre posthume du Maître

LE TESTAMENT D’ICARE

Conférence donnée en 1985 à la Chapelle romane de

SAINT-CÉZAIRE sur SIAGNE

Voilà maintenant deux ans qu’Igor Markevitch nous a quittés, laissant derrière lui cinquante années au service de la musique. Remarqué par Alfred Cortot en 1925 alors qu’il n’avait que 13 ans, devenu son élève et celui de Nadia Boulanger à 14 ans, le voilà catapulté à 16 ans dans le sillage de Diaghilev qui lui commande en 1928 un concerto pour piano qui sera créé à Londres avec Igor Markevitch lui-même au piano le 15 juillet 1929.

Pendant toutes les années trente, Igor Markevitch crée une série d’œuvres qui ont une audience mondiale et généralement saluées comme des étapes importantes de la musique, le compositeur étant crédité de génie.

De ces œuvres créées entre 1929 et 1941, de 17 à 29 ans : le ballet « Cantate » sur un texte de Jean Cocteau, en 1930, suivi d’un « Concerto grosso », puis, en 1931, d’une « Partita pour clavier et orchestre » et d’un ballet « Rébus » pour Léonide Miassine. En 1932, encore un ballet, cette fois pour Serge Lifar, « L’Envol d’Icare » ; en 1933 le « Psaume » pour soprano et orchestre ; en 1935, l’oratorio « Le Paradis perdu » ; en 1937, le « Nouvel Âge » ; et en 1940 la sinfonia concertante « Lorenzo il magnifico » sur des poèmes de Laurent de Médicis. Enfin, en 1941, les « Variations », « Fugue et envoi sur un thème de Haendel », la seule œuvre d’Igor Markevitch que l’on puisse trouver dans le commerce puisqu’elle a été enregistrée par le pianiste Fujii en 1982 et sur l’autre face « Stefan le poète » impressions d’enfance pour piano (1939) enregistré également par le pianiste Fujii.

Ces « Variations » pour piano sont la dernière grande composition d’Igor Markevitch, qui cessa ainsi de composer à 29 ans.

Après 1945, il se consacre à la direction d’orchestre, ce qui lui assurera une renommée mondiale, le mettant au nombre des grands interprètes de ce siècle. Cet aspect, je veux dire « Igor Markevitch, chef d’orchestre » est la pointe la plus connue, je dirai la plus évidente, de l’iceberg Markevitch. Il était le « Prince Igor », comme on aimait l’appeler se référant à la souveraine aisance de sa gestique où la sobriété et la précision le disputaient à une sensibilité d’une rare intensité. Entre mille, pensons à la restitution de la « Création » de Haydn, de « Daphnis et Chloé », du « Sacre du Printemps », voire de « La Vie pour le Tsar » de Glinka.

Mais la gloire du chef d’orchestre a éclipsé l’œuvre du compositeur qui pourtant eut son heure de gloire et fut célébré comme un génie.

Des musicologues comme Henri Prunières, Pierre Souvtchinsky ou Boris de Schloezer, des chefs d’orchestre comme Scherchen, Koussevitzky ou Karel Ancerl, des compositeurs comme Bela Bartok, Francis Poulenc, Florent Schmitt, Henri Sauguet, Darius Milhaud, Jacques Ibert, Dallapicola saluent l’apparition des œuvres du jeune Markevitch.

Après l’audition d’ « Icare », Bela Bartok âgé alors de 52 ans écrit à Markevitch qui en a 22 :

« Cher Monsieur, permettez à un collègue qui n’a pas l’honneur de vous être connu, de vous remercier pour votre merveilleux « Icare ». J’ai nécessité du temps pour comprendre et apprécier toute la beauté de votre partition et je pense qu’il faudra beaucoup d’années pour qu’on l’apprécie. Je veux vous dire ma conviction qu’un jour on rendra justice avec sérieux à tout ce que vous apportez. Vous êtes la personnalité la plus frappante de la musique contemporaine et je me réjouis, Monsieur, de profiter de votre influence. Avec ma respectueuse admiration. Bela Bartok. »

Henri Prunières, le fondateur en 1919 de la « Revue musicale », écrit en 1933, après la première audition de « L’Envol d’Icare » :

« Ce qui m’a le plus frappé…, c’est moins son évidente originalité de forme que le dynamisme qui l’anime et la poésie dont il déborde. Pas de sentimentalité, aucune sensualité. Une musique nue, pure comme le diamant, qui reflète une sensibilité pudique mais interne. On est loin des jeux, des petits amusements, des déclamations. »

Lors d’une exécution du « Psaume » à Florence, Dallapicola dira :

« Le ‘Psaume’ fait partie de ces œuvres qu’on croit marginales jusqu’à ce qu’on s’aperçoive qu’elles se plaçaient au centre de leur temps. »

Il est bien entendu trop tôt pour faire des bilans, des comparaisons d’influences. La musique de Markevitch doit faire pour cela partie de notre univers sonore, ce qui n’est pas encore le cas. Vous dire que je suis persuadé qu’Igor Markevitch avec une vingtaine de ses opus est un des grands compositeurs de notre siècle – n’est encore rien dire, car je puis être soupçonné de piété filiale et d’être ainsi aveuglé par mes sentiments affectifs. C’est pour cette raison que je m’effacerai le plus possible pour laisser parler les faits, les musicologues avertis et bien entendu, dans la mesure du temps imparti, la musique d’Igor Markevitch.[1]

Le « Nouvel Âge », créé le 21 janvier 1938 à Varsovie, me semble annoncer d’une certaine manière le climat du « Concerto pour orchestre » de Bartok qui est de 1943. Un même champ problématique sonore et rythmique frappe encore ma sensibilité musicale.

Le « Nouvel Âge » joué à Paris en 1938, sous la direction d’Hermann Scherchen, provoqua des articles indignés dont le plus outré revient à la plume de Lucien Rebatet dans l’Action française du 25 novembre 1938 où cette œuvre était traitée d’ « ignoble crachat », d’ « attaques épileptiques » :

« Derrière ce vacarme obscène ou ce flasque étirement, il n’y a pas une idée perceptible ; rien qu’une impuissance qui serait presque pitoyable si elle était moins répugnante. J’ignore tout des origines de M. Markevitch, sauf qu’il vient de quelque Russie. Mais, pour le coup, en voilà un qui par le seul aspect de sa musique réunit toutes les probabilités du judaïsme. Quel sens attribuer à cette infâme bouillie, cette impudente frénésie sinon celui du sabbat juif, grimaçant et grinçant ? »

Je voudrais maintenant vous parler de trois autres œuvres d’Igor Markevitch : le « Psaume », l’oratorio « Le Paradis perdu », enfin « Icare ».

Nous verrons comment Markevitch le compositeur et Markevitch l’homme sont étroitement imbriqués, non pas du point de vue du déroulement anecdotique de la vie mais de cette confrontation entre les orientations essentielles de la musique et les vecteurs forts de la vie se dessine un premier portrait du créateur-Markevitch.

Ce n’est pas une chose aisée de tracer un tel portrait, tant de facettes y chatoient : compositeur, chef d’orchestre, théoricien et pédagogue de la direction d’orchestre, écrivain et philosophe (ses mémoires Être et avoir été), musicologue[2], penseur[3]. Où est le vrai Igor Markevitch ?

Lui-même s’étonnait que les autres lui donnassent plusieurs visages-personnalités, alors que lui se voyait intérieurement toujours le même.

Or ce qui frappait les autres, c’était souvent le hiatus, parfois même l’abîme qui pouvait exister entre les « différents Igor Markevitch ».

Dimension schizoïde d’un grand artiste. Cela explique qu’il ait pu passer sans transition du sublime à des colères disproportionnées avec leur objet ou à des actes frisant la mesquinerie. Cela explique aussi l’état de perpétuelle inquiétude dans lequel se trouvait ce novateur, novateur dans la création musicale et l’art de diriger.

Le « Psaume » pour soprano et petit orchestre a été créé le 30 novembre 1933 avec l’Orchestre du Concertgebouw conduit par le jeune compositeur de 21 ans et chanté par Vera Janacopoulos, la musique écrite sur un texte français établi par Igor Markevitch à partie des psaumes 8, 9, 59, 102, 148 et 150.

La beauté complexe de cette œuvre a été commentée diversement.

Gabriel Marcel, après s’être plaint de la cacophonie fatigante du « Psaume », cette façon de rendre la musique paroxystique dans la ligne du « Sacre du Printemps », conclut :

« Il n’y a pas, semble-t-il, de musique à laquelle le sens de la grâce ait été plus radicalement refusé. »

A l’opposé, Florent Schmitt note la volonté du jeune compositeur de se débarrasser de toute couleur et brillance orchestrales.

Et Henri Prunières de déclarer dans Le Temps du 15 mai 1934 qu’il ne s’agit pas de musique religieuse dans le sens traditionnel.

Igor Markevitch fait dans Être et avoir été les remarques suivantes à ce propos :

« Il y a lieu de dire ici mon étonnement de ce que le « Psaume » parût tourmenté, sans doute à cause de la nouveauté du langage. Aujourd’hui, le temps aidant, y prédominent l’exaltation peut-être, mais aussi la sérénité. Avec le recul, je vois cette œuvre m’ouvrir la voie, laquelle après de longs cheminements me conduirait un jour à un agnosticisme libérateur. C’est elle qui m’attacha à la signification du Paradis Perdu, avec l’apparition en l’homme de l’homme, sa mort relative symbolisée par la perte de son innocence, suivie de sa naissance réelle. J’ajoute que dans l’évolution que cette expérience ouvrit, je ne renierais jamais la métaphysique, cette plus haute des institutions humaines, sans laquelle l’énergie vitale n’aurait plus aucun sens. »[4]

Le fait même d’avoir écrit le texte en français et non dans une des langues sacrées liturgiques, le fait de le donner dans la langue du pays où l’œuvre est jouée, indique à lui seul et souligne de façon exotérique ce que nous apercevons encore de la personnalité de Markevitch à travers le « Psaume » : sa dimension cosmopolite[5] – dimension cosmopolite qui rejoint le cosmopolitisme évident d’Igor Markevitch.

Déjà sa généalogie comporte des Serbes, des Ukrainiens, des Russes, des Suédois.

Russe et Ukrainien par la naissance, puis par une prise de conscience de plus en plus aigüe au fur et à mesure qu’il avançait dans la vie, Suisse d’adoption depuis l’âge de deux ans. Ce pays « fut un des lieux privilégiés de la formation intellectuelle, des amitiés fécondes avec Alfred Cortot, Elie Gagnebin, Charles Faller, Ramuz, le lieu des randonnées, de la vie quotidienne, des séjours bénéfiques après les fatigues des voyages à l’étranger. C’est en Suisse, à Corsier en particulier, qu’ont été écrites la plupart de ses œuvres principales . Voir « Igor Markevitch et la taille de l’homme » programme du concert de Corsier 16 octobre 1982.

Italien aussi. Se retrouvant au moment de la guerre en Italie, profitant de l’amitié de l’historien de la Renaissance Bernard Berenson et concevant en 1940 une sinfonia concertante pour soprano et orchestre « Lorenzo il magnifico » sur des poèmes de Laurent de Médicis, participant à la résistance contre les fascistes et écrivant en 1943 en italien un « Hymne de la libération nationale », cette période se reflète bien dans son premier livre de mémoires « Made in Italy », Genève 1946

Français d’élection enfin.

Je me souviens encore du visage illuminé d’Igor pendant l’été 1982, quelques mois avant sa mort : il avait été reçu par le Président de la République François Mitterrand et avait obtenu, sans les formalités habituelles, la citoyenneté française.

Je l’ai vu juste après cette réception, heureux comme un enfant qui a reçu un cadeau longtemps désiré. Toute sa personne était détendue et dans un état de grâce, ce qui était rare chez lui à cause de la multiplicité de ses occupations, préoccupations et soucis.

Igor Markevitch a eu la capacité d’assimiler les diverses cultures européennes. En cela même, il est profondément russe, si l’on en croit Dostoïevski qui a développé à plusieurs reprises, dans son roman « L’Adolescent » et dans son célèbre discours de 1880 sur Pouchkine, l’idée selon laquelle le Russe était en Europe celui qui pouvait le mieux s’identifier aux différentes cultures européennes, tout en restant par là-même profondément russe. Être russe, selon Dostoïevski, c’est être pan-humain.

Mais le statut particulier du Russe Igor Markevitch, par rapport, par exemple, à Igor Stravinsky, c’est qu’il est, comme l’a bien noté dès 1930 Darius Milhaud, à propos du « Concerto grosso », un Russe sans lien immédiat avec son pays. Il avait deux ans lorsque ses parents partirent de Russie et il n’y revint que dans les années 60.

Cela pourrait expliquer, selon Milhaud, la sublime violence, l’explosion ininterrompue, l’émotionnalité ébouriffante de tel passage de sa musique. Alors que le trait distinctif du génie de Stravinsky jusqu’à l’opéra « Mavra », c’est-à-dire pendant toute l’époque diaghilevienne, aura été le rapport étroit au folklore russe.

Avec Igor Markevitch, et je rapporte ici encore les propos de Darius Milhaud dans L’Europe du 13 février 1930, il s’agit d’une grande musique intemporelle, sans superficie, pittoresque, où l’instrumentation est d’une richesse incroyable.

Je prendrai l’exemple de la collaboration de Ramuz avec Stravinsky et avec Markevitch : avec le premier – « L’Histoire du soldat », avec le second « La Taille de l’Homme ». Pour Stravinsky, Ramuz a puisé dans le trésor des contes populaires russiens et a écrit son texte de « L’Histoire du soldat ». Pour Markevitch, il compose un poème dont l’inspiration dépasse les sources folkloriques, dans une vision globale de la place de l’Homme dans l’Univers.

C’est là le problème de toute l’œuvre d’Igor Markevitch et de la difficulté de sa réception. C’est là si l’on veut le côté négatif de son cosmopolitisme, car forte est la propension de la critique et du public à ranger dans des cadres connus.

La musique d’Igor Markevitch n’appartient pas directement à l’Histoire de la Musique russe, même si elle n’aurait pas pu naître sans « Le Sacre du Printemps », même si elle assimile l’héritage de Scriabine. Elle n’appartient pas non plus de façon évidente à la musique française. On doit donc la recevoir telle qu’elle est, dans son intemporalité qu’il faut comprendre non comme un avatar de « l’art pour l’art », mais plutôt comme la création, à travers les structures offertes par l’époque contemporaine, d’un tissu musical

« ivre du mystère, trouant les nuages de l’esprit et de la musique »,

selon l’expression d’Hermann Scherchen.

Le critique Léon Kochnitzky a été certainement injuste lorsqu’il écrivit dans Marianne le 27 juillet 1938 que la musique de Markevitch était un contrepoint de thèmes que la jeunesse de notre époque a établis, sans différence de race, de nation et de classe.

« La Paradis perdu » est un oratorio en deux parties pour soprano, mezzo-soprano, ténor, chœur mixte et orchestre, créé à Londres en 1935 par l’Orchestre et le Chœur de la BBC sous la direction du compositeur.

Le texte avait été écrit par Igor Markevitch d’après Milton. Il s’agit d’une œuvre capitale extraordinairement belle et stricte, inexorable et parfois inhumaine, selon Darius Milhaud dans Le Jour du 26 décembre 1935 qui parle d’un climat proche des gamelans, les orchestres de Bali et de Java et des psalmodies extrême-orientales.

La musique extrême-orientale avait intéressé Debussy lors de l’Exposition Universelle de 1889 où il avait visité le Théâtre annamite.

Paris eut son Exposition coloniale internationale en 1931 où des « spectacles exotiques » faisaient connaître le Théâtre annamite, les musiques et les danses du Cambodge, de Thaïlande et de Bali et elle semble aussi avoir eu un écho dans la musique d’Igor Markevitch dès « L’Envol d’Icare ».

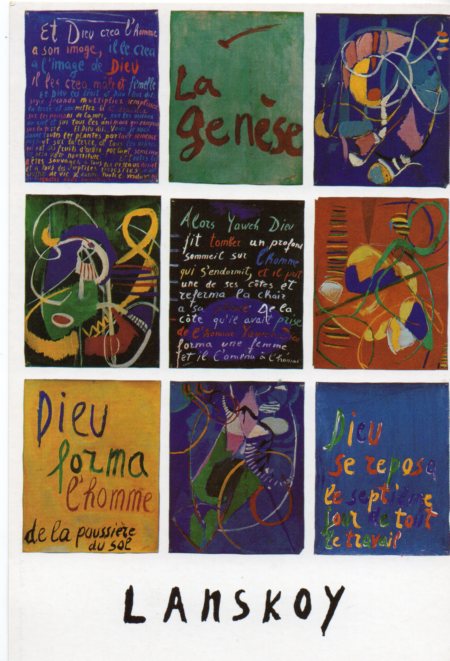

« Le Paradis Perdu » nous révèle tout un pan de l’Homme Markevitch, son écartèlement entre la culture chrétienne dont les fruits magnifiques lui paraissent empoisonnés et l’annonce d’une genèse de l’homme, d’un nouvel humanisme qui, pour autant qu’il nie la spiritualité chrétienne, ne se détourne nullement des Forces métaphysiques qui agissent sur l’Univers.

Se défendant de tout mysticisme de type chrétien, Igor Markevitch n’a cessé, à la suite de Schopenhauer, de voir dans la musique « une métaphysique sensible ».

Dans son « Introduction au Paradis Perdu »[6], il formule cela ainsi :

« Se développant lui-même dans le temps qui passe, l’art de la musique est capable de nous livrer au grand jour, avec son connu divin, un morceau de cet éternel présent que j’ai appelé une seconde dimension du temps, d’être en d’autres termes, « une vérité faite de sons ». « Métaphysique sensible », autrement dit « vérité faite sons », était-ce là une impasse expliquant l’arrêt de la création musicale, comme on l’a avancé ?[7] Peut-être.

Igor Markevitch avait nettement le sentiment que mille ans de musique venaient à leur fin et que ce qui venait à la suite et s’appelait « musique » était autre chose que cette « métaphysique sensible ».

On peut se demander si Igor Markevitch a vu juste et en débattre un jour.

En tout cas, nous devons constater qu’aucune nécessité intérieure ne l’a poussé à créer.

« Icare », sans doute la plus célèbre œuvre d’Igor Markevitch, a été d’abord conçue comme un ballet destiné à Serge Lifar et portant le titre « L’Envol d’Icare ». Cette version fut créée le 26 juin 1933 à la Salle Gaveau par l’Orchestre symphonique de Paris sous la direction de Roger Desormière. Puis, en 1943, Markevitch recomposa cette œuvre et lui donnera son aspect définitif. Il s’est non seulement identifié au mythe d’Icare tel que la Grèce nous l’a transmis, mais il en a fait son propre mythe au point de vouloir appeler le dernier livre qu’il ait livré à la postérité et que nous avons fabriqué ensemble Le Testament d’Icare .

Comme la musique de Markevitch, ce livre ne peut s’assimiler qu’avec le temps. Il est comme un contrepoint de l’œuvre musicale, voire son filigrane.

Markevitch-Icare, c’est à la fois l’envol, l’enthousiasme, l’arrachement à la terre, la plongée dans le mystère du monde, c’est aussi l’audace de celui qui vainc toutes les pesanteurs terrestres, donc un transgresseur de l’humanité moyenne. Mais corollairement au « couronnement de l’expérience » que représente l’aventure d’Icare, il y a la mort, mais, dans la volonté consciente de Markevitch, cette mort n’est pas un moment négatif, une défaite ; chez lui il n’y a pas chute comme dans la tradition grecque. L’exemple le plus frappant de cette tradition dans la pensée européenne est « La Chute d’Icare » de Breughel où Icare est même ridiculisé.

Markevitch écrit :

« Dans ‘Icare’ on retrouve quelque part ses ailes, comme les restes d’un serpent qui a fait peau neuve. Ce sont les signes de renouveau. »[8].

Icare est comme « le papillon amoureux de la lumière » qui « vient se consumer sans la flamme de la chandelle ». Markevitch cite encore la Goethe de « La Nostalgie bienheureuse » :

« Tant que tu n’auras pas compris ce ‘Meurs et Deviens’, tu ne seras qu’un hôte obscur sur la terre ténébreuse ».

Dans « Faust », « la victoire naît d’une défaite où l’orgueil abdique devant notre faculté productrice, symbolisée par l’Êternel Féminin. Alors nous pouvons dominer notre existence en contribuant au travail du monde sur nous, c’est-à-dire nous intégrer à un Tout qui nous enrichit par sa grandeur ».

« Icare », c’est donc, d’une certaine façon, selon la volonté créatrice de son auteur, une autre façon de dire « Mort et Transfiguration ». Mais comme dans toute grande œuvre, il y a ce qui échappe à la conscience même de son auteur, ce qui apparaît comme y étant celé et scellé, ne se découvrant que peu à peu et jamais de toute façon entièrement. Dans ce sens « Icare » dissimule peut-être la clef d’un secret markevitchien. Le Maître a-t-il cessé de composer parce qu’il avait brûlé trop vite ?

Icare, c’est aussi le mythe de la brûlure. Et le vocabulaire courant nous offre bien des images de cette consumation.

Dès 1936, le sentiment de la critique, à la fois étonnée et agacée, est qu’Igor Markevitch a déjà écrit ses chefs-d’œuvre et a découvert dès les premières œuvres un nouveau monde sonore. Il serait vain, à mon avis, de spéculer sur l’arrêt de la création chez Markevitch : qu’il s’agisse d’un tarissement parce que l’essentiel à dire avait été dit, qu’il s’agisse d’un refus de subir jusqu’au bout la condition d’artiste, à la merci d’un mécénat en voie de disparition ou d’une nouvelle orientation de la musique non acceptée, peu importe. Nous devons prendre tel quel le fait que le compositeur Markevitch ait voulu dire à un moment donné, autrement que par l’écriture musicale, la musique. Il faut lever les obstacles qui empêchent encore que cette œuvre musicale totalement originale soit jouée et enregistrée.

Malheureusement Markevitch a su se créer dans le milieu musical de nombreuses inimitiés. Autant sa vie est jalonnée de grandes amitiés, autant elle est parsemée de litiges, de contentieux, d’ « affaires ». Igor Markevitch a lui-même écrit, lorsqu’il relate la façon grossière dont il avait traité le compositeur Vittorio Rieti :

« Quelques mufleries de ce genre entachent malheureusement une vie ».

Les meilleures formations, les meilleurs solistes et les meilleurs chefs devront comprendre l’importance de la musique de Markevitch :

« On n’a pas toujours Birgit Nilsson comme soliste ».[9]

Igor Markevitch aussi a relativement peu travaillé à mettre en valeur son œuvre : orgueil non dissimulé, tout pénétré de vieille tradition noble selon laquelle l’homme sait ce qu’il se doit … et ce qu’on lui doit :

« On s’étonna dans mon entourage du peu de hâte que je montrais pour faire jouer ma musique. Je me disais pour « Icare » ce que je me suis dit plus tard pour l’ensemble de mon œuvre : si elle a de la valeur, elle peut attendre, et si elle ne peut attendre, il est inutile qu’on la joue. »[10]

La précocité non plus d’Igor Markevitch n’a pas joué en sa faveur. Si, en effet, beaucoup de contemporains, parmi les meilleurs esprits et les meilleurs connaisseurs ont crié au génie, il y a eu parallèlement tout un courant qui a été agacé par cette trop impudente précocité et l’ont trouvée suspecte. Stravinsky n’a-t-il pas dit du jeune compositeur qu’il « n’était pas un Wunderkind, mais un Altklug ». Ce dernier mot étant péjoratif en allemand et équivalent à peu près à « malin comme un singe ».[11] Un critique trouve que

« cette bizarre maturité est périlleuse. Où est la fraîcheur juvénile, l’eau de source agreste qui permet de tenter un long voyage, de s’abreuver, de se renouveler ? »

Cela tient de ce que j’appelle la mythologie de la création qui pense qu’il y a des modèles… Pourrait-on arriver à débarrasser notre réception des œuvres de toutes les considérations adjacentes, en particulier des spéculations sur la « précocité suspecte » ou sur l’arrêt de la production. Sommes-nous capables de juger une œuvre telle quelle ? C’est à ce défi que nous appelle l’œuvre musicale de Markevitch.

Enfin, dans le passage uniquement orchestral de « Laurent le Magnifique », Contemplation de la Beauté, plus qu’ailleurs on sent combien la fonction de la musique n’est pas d’imiter la réalité :

« Il ne s’agit aucunement pour la musique d’imiter la réalité ».[12]

Ce passage dit, plus que toute parole, le site, la hauteur visitée un jour par Igor Markevitch.

Dans ce site où, du temps de Laurent de Médicis, a séjourné le néo-platonisme de Marsile Ficin, le rythme se fait harmonie céleste et nous permet d’entendre le silence.

Jean-Claude Marcadé

1985 – Saint-Cézaire – Bordeaux

[1] « Bien entendu » ici dans ce n°, nous avons pensé devoir ne pas reproduire les passages de la conférence où Jean-Claude Marcadé annonçait et commentait les extraits des œuvres des œuvres du Maître enregistrées qu’il nous a donnés à entendre.

[2] Edition encyclopédique des symphonies de Beethoven

[3] Le livre de pensées et aphorismes que nous avons fait ensemble Le Testament d’Icare , mais aussi dans le flux du quotidien : amant, époux, père, ami, maître de maison, seigneur ou despote

[4] P. 301

[5] Et je ne dis pas, intentionnellement, « universaliste », ce serait une redondance car toute œuvre d’art authentique est bien « universaliste

[6] Musica Viva, avril 1938

[7] Claude Tannery in Libération 1/IV 1983

[8] « Être et avoir été » p. 236

[9] Citations de « Être et avoir été », p.292, p.300

[10] O.C. p.250

[11] Vera Stravinsky, Robert Craft, « Stravinsky in pictures and Documents « , London 1979, p.166

[12] O.C. p.301